"It's not just about academic integrity—it's about mourning what we've lost."

Last week, I found myself in a meeting with yet another faculty member wanting to discuss what to do about her AI policies. The conversation followed its predictable arc: concerns about cheating, laments about the "death of writing," and eventual resignation that we can't stop this technological tide. But this time I actually heard the sense of loss behind the practical concerns in a way that I hadn’t before. I knew there was mourning taking place behind the scenes, of course, but I hadn’t heard it quite like this.

When Resistance Is Actually Mourning

While reading The Spirituality of Imperfection by Ernest Kurtz and Katherine Ketchum, I stumbled upon the Greek term lypē (λύπη)—a concept that describes not just sadness, but a cultivated sorrow, an emotional looping in fantasies about how things used to be. Drawing on the theologian Evagrius Ponticus, the authors describe it as a form of destructive thinking.

And suddenly, I found myself writing in the margin: #AIResistance movement.

At the risk of being chatbot like and making connections where none exist, I’m going to hold forth on this: What if resistance to AI is a form of existential envy—not jealousy of another's gain, but anguish over a perceived loss?

In higher ed settings, I see this in conversations with faculty who feel disoriented by AI-assisted writing embedded in every word processor, email platform, and browser. Often their resistance is positioned as concerns about academic integrity, but I think that’s presenting as a kind of secondary concern masking the “loss” itself. Something deeply familiar is actively eroding in front of our eyes ... the messy, analog process of learning to write and think. The struggle.

As someone who fell in love with the process of the struggle, I, too, mourn its departure. AND I can also see it as something else (thanks in part to my new experience with dialectical behavior therapy, lol).

The Binary Beneath the Argument

In the (admittedly algorithmically defined) circles I run in, I am seeing many conversations around generative AI charged with a passion that goes beyond the argument about academic integrity. The rhetoric I see has two key characteristics: (1) It’s binary and (2) It’s passionate. Too passionate for the kind of theoretical arguments academics usually have. Whether it’s the #AIResistance movement or the quiet frustrations voiced by faculty, there is a palpable mourning of what teaching and learning "used to be."

Some grieve the loss of handwritten rough drafts, labor-intensive revisions, and the messy, beautiful struggle of coaxing ideas into shape. There are worries about the lack of student authorship, the flattening of voice, the ease of the shortcut. And they're right to notice what's shifting.

But when critique morphs into nostalgia,

and nostalgia calcifies into resistance,

we risk mistaking memory for principle.

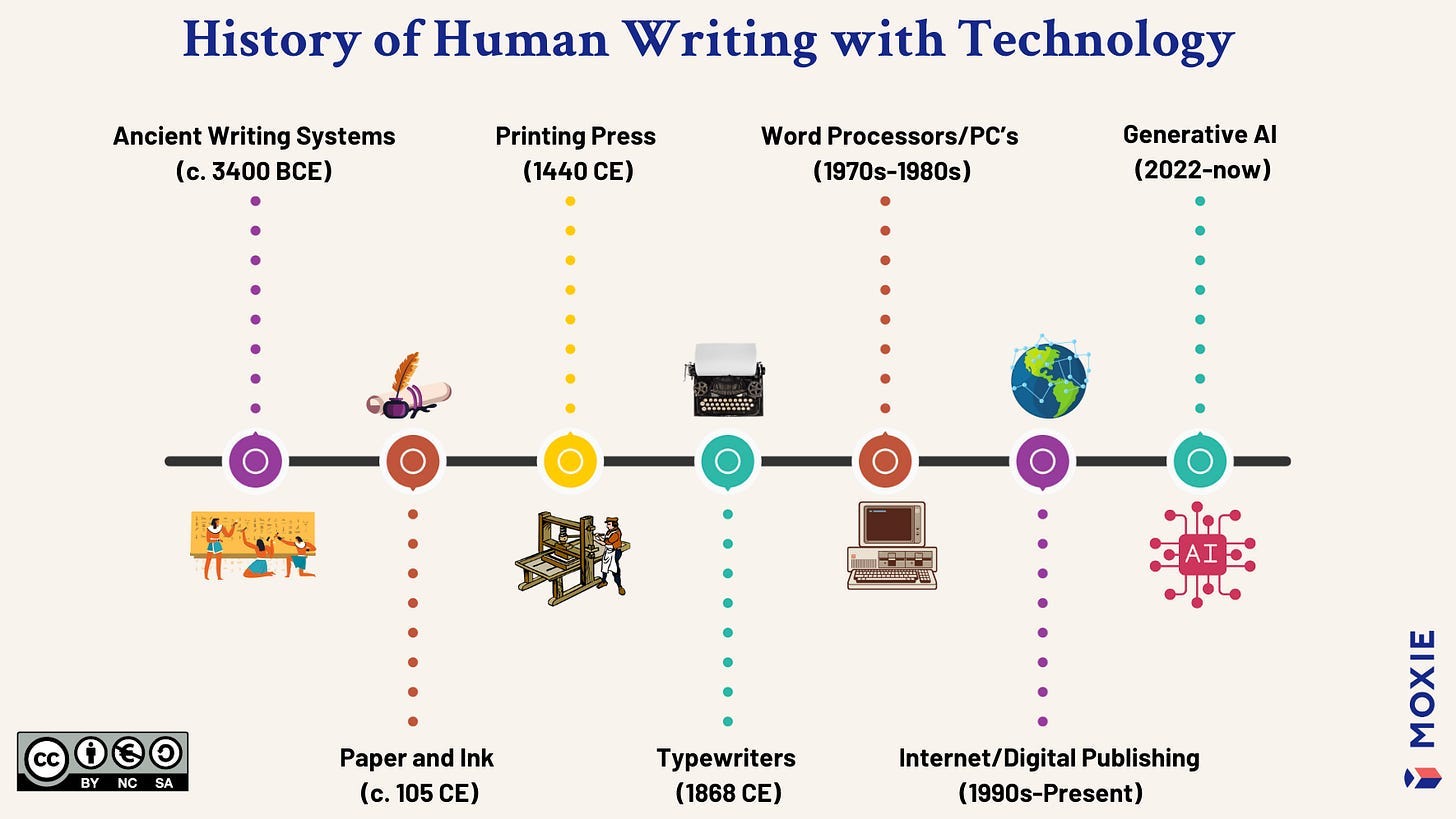

This isn't new. English teachers once lamented the typewriter. Then the word processor. Then the spellchecker. Then Wikipedia. Then Grammarly. The current wave of AI is just the latest in a long arc of technological evolution that has always disrupted writing instruction.

The difference now is the scale. Generative AI isn't just changing how we write—it's changing how we think about writing. And for many educators, that change is destabilizing. But the emotional response isn't necessarily about AI itself. It may be about loss. And that loss, when unacknowledged, becomes envy in its ancient sense: an aching fixation on what used to be.

So, how do we respond?

With rejection and dismissal? Get with the times, people!

With uncritical acceptance? If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em!

I propose with discernment.

Discernment invites us to see clearly: to acknowledge what is shifting, name what is valuable, and let go of what no longer serves. It asks us to balance intellectual humility with professional courage. It recognizes that the past mattered—but it doesn't mandate our future.

As educators, scholars, leaders, our task is not to replicate the conditions of our own learning ...

It's to meet this moment with clarity and purpose.

Acceptance, in this context, doesn’t mean resignation. It means clarity. Clear is kind, as Brene Brown says. Kind to others and, the part we often forget, kind to ourselves. Radical kindness of the type that can’t co-exist with denial, dismissal, and distortion. It is from that place that we can build assessment systems that don’t just react to AI, but actively teach students what deep thinking looks like—because that’s something AI can’t fake.

Rubrics as Resistance: A Framework for Responding with Clarity

If we’re going to survive this shift—and I mean that without hyperbole—we have to give loss its due. But we can’t live in it. Moving forward means accepting the reality of GenAI-augmented student writing and responding with insight, not indignation.

Moving forward means acceptance + responding with insight, not indignation. One way to do that is by refining how we evaluate writing—not just to spot cheating, but to clarify what real writing growth looks like.

The framework I have presented comes from second language writing research, where scholars evaluate writing across three dimensions: Complexity (or Depth), Accuracy, and Fluency—often referred to as the CAF model (here’s a solid academic source if you need one). I’ve adapted it for native and non-native writers alike because, frankly, academic writing functions like a second dialect for many students.

Here’s a simplified version of how I frame it:

Depth (Complexity): Range of ideas, sources, and analytical thought

Flow (Fluency): Smooth expression and logical connection of ideas

Accuracy: Mechanics like grammar, punctuation, and citation format

As a linguist concerned with the connection between writing and thinking, my two cents is this:

We should be outsourcing a lot more of the accuracy work to technology. Grammar, spelling, even basic citation formatting—these are tasks where AI excels, and where human energy is arguably wasted. Likewise, when it comes to fluency—sentence structure, logical flow, and coherence—there’s no reason not to collaborate with AI to get closer to polished output.

But there’s one area where the human touch can’t be replaced: depth. Complexity of thought. Authentic reasoning. Nuanced stance. These are the markers of meaningful academic writing—and they remain uniquely human.

So our rubrics should reflect this hybrid reality. Let the machines help with polish. Let the human mind shine through complexity.

These categories help make the invisible more visible. They give us a way to name what’s often missing from AI-generated work: depth of reasoning, authentic stance, and insightful synthesis. The visuals above offer real examples of how these distinctions show up in writing.

Let’s Problematize This Crazy Idea

Still, I get it. For many educators—especially those who don’t teach writing—this might all sound too abstract or idealistic. So let’s name some valid concerns:

❓1. Is rubric revision enough?

Isn’t this just a cat-and-mouse game? If we revise the rubric, won’t students (or bots) just optimize it?

My response: It’s a risk, yes. But opaque grading invites workarounds; transparency invites participation. By showing students what counts (i.e., depth of analysis, use of evidence, clarity of reasoning) we’re giving them tools to use, not traps to dodge. Good rubrics don’t eliminate cheating; they raise the bar for thinking.

❓2. Can faculty actually use these rubrics?

What about instructors without writing pedagogy backgrounds?

My response: This is a challenge and an opportunity. Rubrics informed by linguistics don’t need to be jargon-heavy. They just need to be observable. Think: What are the specific words or phrases in this claim that show original thinking? What might a person write to engage more deeply? These are questions any faculty member can engage with—with the right scaffolds:

What are the observable linguistic markers of deep engagement and critical thinking?

Use of stance markers such as hedges (e.g., might suggest, could indicate, appears to) shows nuance and critical distance. One thing we know from linguistic research is that novice writers (e.g., first-year college writers) often boost more than they hedge. So does Donald Trump. What’s more, Chatbots do too, especially advanced GenAI models like GPT-4, Gemini Ultra, and Meta AI. While they may not boost, they project high confidence through other linguistic strategies for conveying certainty, often leading to overconfidence even in uncertain contexts.

Strategic reporting structures (e.g., X asserts that..., This finding supports the view that...) align with scholarly conventions. A recent study found that human writers use these to build argument chains; AI writing tends to remain surface-level and overgeneralized.

From the Manchester Academic Phrasebank, here are sentence starters that reflect original or critical thinking:

A weakness of this is...

This suggests a need for...

It could be argued that...

An alternative interpretation might be...

While this approach has merit, it also...

One implication of this finding is...

This raises questions about...

These aren’t complicated. But they are cognitively revealing. They’re difficult to use meaningfully without thinking—and that’s precisely the point. They could be used as “come sit in my office and let’s talk about this paper you wrote” conversation starters or questions to dig a little deeper into a student’s thinking.

❓3. What about equity?

Will this disadvantage students still building confidence, especially multilingual writers?

My response: On the contrary, this approach can support equity. When we value depth and complexity over rote correctness, we give multilingual and neurodiverse students more entry points into success. Plus, understanding writing as a skill (not just a reflection of intelligence) helps all students grow.

❓4. Where does this leave grading?

If we shift from correctness to criticality, will grades get even more subjective?

My response: Not if we get clear on what we’re measuring. Rubrics rooted in functional literacy give us anchor points: idea development, coherence, engagement with evidence. The goal isn’t to eliminate subjectivity—it’s to discipline it. To make our judgment visible, explainable, and consistent.

Final Reflections

This isn’t just a call for better tools. It’s a call for better thinking about what writing is, what it does, and how we help students develop it, from one human mind to another. By grounding ourselves in a clearer understanding of what effective academic writing actually entails, we de-risk the reality of our current pandemic: Synthetically polished submissions that are precise, fluent, and (usually? often?) suspiciously devoid of genuine intellectual struggle.

The symptoms of this pandemic point us in the direction of placing less value on what AI-generated writing tends to mimic well—fluency and accuracy—and enhanced value on what it tends to lack: depth, stance, nuance, and authentic engagement.

These abstract distinctions can be made visible. So rather than doubling down on unreliable detectors that undermine trust, we can hedge our bets on the power of improved rubrics—the kind that reward uncertainty when it’s appropriate, value reasoning over polish, and make visible the difference between syntactic complexity and intellectual risk-taking.

p.s. Here’s a Google Doc with a sample rubric.

Thank you for writing this. It highlights so many important aspects of this particularly sticky conundrum. It also points to a lot of opportunities. Whenever I hear these conversations about how AI reduces depth and cheapens the thought process, I feel a little pang, because I know how needless that loss is. When we engage with generative AI additionally, turning to it to actually deepen our thought process, challenge us, introduce new ideas, for consideration, and contribute to our creative process in ways that only it can, the results can be amazing, even breathtaking. The scope of new information, new ideas, and new ways of combining them with you holding established is to substantial to dismiss. There’s just so much there, if we know how to work with it, responsibly, collaboratively, as leaders, not followers, about the technology. This definitely deserves some more detailed explanation. Let me add that to my list of projects before the end of this month, :-)

I loved this piece, Jessica and Kimberly. Your grief framing of faculty resistance really hit home. As a student, it can be hard to see things from the other side, but this helped me understand it in a new way.

You asked, “Can we value complexity over correctness?”

I just want to say: Yes. We have to.

If we want to be ready for the future of work, complexity, collaboration, and critical thinking must be at the center. I really appreciate the focus on depth as something we build together as a class, not just something we’re judged on alone. Thanks for this—it's got me thinking in all the best ways.